I’d like to start talking about the Wii system architecture, including its possibilities, challenges, and limitations. In order to do that, I think it best for me to start by talking about how the Wii software is structured and how software is run. (As always, for more information on the subject, please see the Wiibrew Wiki.)

The Wii has two processors inside of it — the main one is called “Broadway”, and is a PowerPC architecture chip that is similar to the one found inside a GameCube (but much faster). When you run a game or navigate through the Wii System Menu — the one with all of the channels — you’re exercising code running on the Broadway.

The other big chip inside the Wii is codenamed “Hollywood”. It’s officially considered to be a graphics chip — it’s the one with the big ATI logo — but as we discovered, there’s much more to it than Nintendo cares to admit. In addition to the graphics hardware and 24MB of RAM, there’s a full-blown ARM core in there that handles I/O and security — Segher nicknamed it “Starlet”.

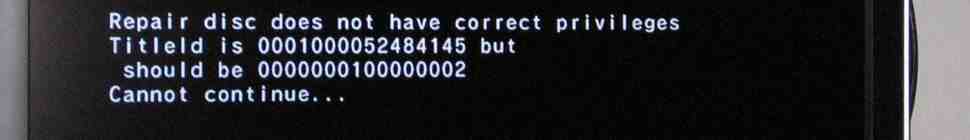

When the Wii turns on, the first thing to actually boot up is the Starlet — although you can’t see it happen. It has three stages of bootloader — boot0, boot1, and boot2 — and then it opens up the internal NAND storage of the Wii to look for the System Menu (aka 1-2 — go read about title IDs to learn what those numbers mean). Once it finds 1-2, it reads a header (the TMD) to find out what version of Starlet firmware it requires, reloads itself, loads 1-2 into memory, and finally powers on the Broadway chip. All of this happens well before the Wii shows anything on your TV.

Once the menu loads, you actually have two pieces of code running at the same time — the system menu code, and the “Starlet firmware” referenced above. That Starlet code has a name — “IOS”. This is a crucial point, and one we will investigate further — just accept my word for the moment that there are several versions of IOS stored on your Wii (19?) but only one of them matters at any given point. When you’re booting, it’s IOS30 (at least, for the time being).

Once the System Menu / 1-2 has started, it displays the “Warning Screen” (“don’t throw shit at your TV, hit A to continue”). Once you’ve made it past that, the System Menu goes and inventories the internal NAND flash of the Wii to see what channels you have installed; it also checks to see if a disc is present in the drive. Once you pick a channel — or try to start a game on disc — the System Menu will ask IOS to handle verifying all relevant signatures, decrypting all code and data, loading it into memory, and finally rebooting the PPC. (There is a lot of rebooting that goes on while you use your Wii — for both chips.)

So what? Well, we’re now at the point in Wii hacking where things get interesting. We know what code runs where; we know what it does, and in many cases we know ways to modify its behavior, including patching the firmware. The problem is that any slight modification in any of the pieces of code I’ve mentioned can easily cause a full bricking of your Wii, with no possible recovery. If you send your Wii back to Nintendo, they’ll probably throw away the main Wii board and give you a refurbed unit … if you’re lucky.

Next up, we’ll talk a bit more about the risks involved, and things we can do to (partially) mitigate them.